On the night of March 28, 1915, Molly Kelly, the chambermaid at the Sovereign Hotel, was so nervous that she went to bed fully clothed. She had only been working at the hotel for two weeks but the gossip among the other employees that the hotel was going to burn down made her afraid. Sure enough, in the early morning hours of March 29, she awoke to the smell of smoke in her third-floor room. She managed to escape unharmed.

Molly Kelly was one of several witnesses for the prosecution in the preliminary hearing of William Shinbane, the former owner of the Sovereign Hotel who was charged with setting fire to his own property.

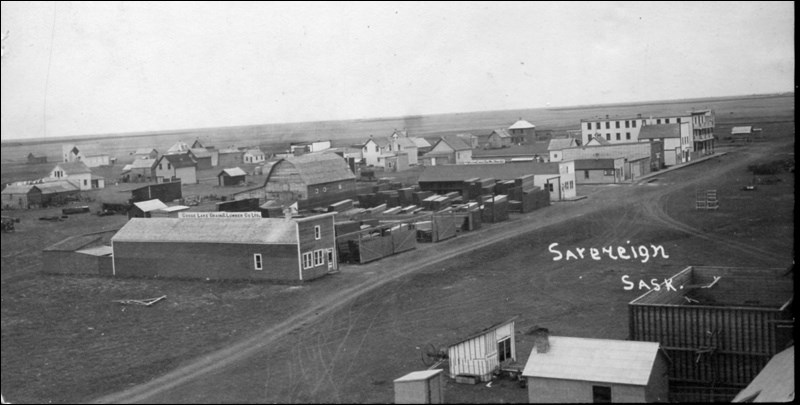

Shinbane emigrated to Canada from Russia as an infant in 1886, settling in Winnipeg where his father ran a general store. He married Anna Schwartz in 1911 and by 1915 they were the owners of the three-story hotel at Sovereign, built in 1912 by Chris Hoeschen of the Saskatoon brewery family. Sovereign is located 26 kilometres southeast of Rosetown on Highway 15.

The Saskatoon Daily Star reported that there had been “a small epidemic” of hotel fires in Saskatchewan after Premier Walter Scott announced on March 18, 1915, that Prohibition was coming to the province starting on July 1. Fires on licensed premises were viewed with great concern by the provinces’ insurance companies. One company representative told the Daily Star, “We saw it coming and most of us believe that this is only the beginning.”

By April 22, six hotel fires in the province, including the one at Sovereign, were under investigation. Several insurance companies cancelled all their hotel policies. “Some [companies] state that under no circumstances will they insure hotels for more than two-thirds of their estimated value,” one insurance man told the Star,Phoenix, “Still others decline in future to carry any insurance of hotels whatever.”

On Nov. 4, 1915, William Shinbane was arrested in Winnipeg and brought to Saskatoon for his three-day preliminary hearing beginning on Nov. 10. The testimony given at the hearing provides a revealing glimpse into the operations of a small-town Saskatchewan hotel prior to Prohibition.

Sam Musik, the Sovereign Hotel’s porter testified that on the night of the fire, he had made up the furnace fire and tended to two dogs that were kept in the cellar. He awoke at 2 a.m., his room so thick with smoke he had to exit the burning building via a rope through the window of his room. Musik learned a couple of days later that the two dogs in the hotel cellar had been removed at ll:30 p.m. by a friend of Shinbane’s. The porter also testified that Shinbane told him he could not pay him his $335 in back wages until he secured the money that was coming to him from the insurance companies.

Mrs. Mitchell, the hotel’s cook, barely escaped the hotel fire with her young daughter. She was awakened by Shinbane calling, “Mrs. Mitchell, for God’s sake get up, there’s a fire in the house.” She lost all her belongings. She testified that for about a week prior to the fire, the Shinbanes had been busy packing up the hotel linens, storing them in boxes on the landing the night before the fire. The smoke was so thick as she descended to the lower floor that she could not see whether the boxes were still there, but she did not run into them during her escape.

All the witnesses for the prosecution stated that they could smell gasoline as they exited the burning building. Sylvester Herrick, hotel handyman, testified that there was a tank of gasoline at the back of the building that was used for gas-lighting purposes in the hotel.

Henry Thomas represented the insurance companies which held policies on the Sovereign Hotel and its contents totalling $23,900. “[W]hile the policies were made out to William Shinbane, the losses were payable to the Hoeschen-Wentzler Brewing Company, Saskatoon, and to Jacob Shinbane to the extent of $13,000 to the former and $10,900 to the father of the accused,” the Daily Star reported.

Despite the defense lawyer’s statement that there was not sufficient evidence to connect the accused with the fire, Inspector Duffus bound Shinbane for trial. Duffus said that while there was no overwhelming presumption of guilt, there was, in his opinion, enough evidence for the case to go to a jury.

And this is where the case goes cold. I have not yet found any newspaper story or other reference revealing what happened regarding Shinbane’s trial. Here’s what I do know. By 1916, according to the Canada census, William and Anna Shinbane and their two boys, Ted and Berel, were living in Swan River, Man., where William worked as a merchant. In the early 1920s, the family moved to Los Angeles, Calif., where William worked as a building contractor. Shinbane died on June 29, 1931 and is buried in Los Angeles.

The hotel at Sovereign was not rebuilt after the 1915 fire.