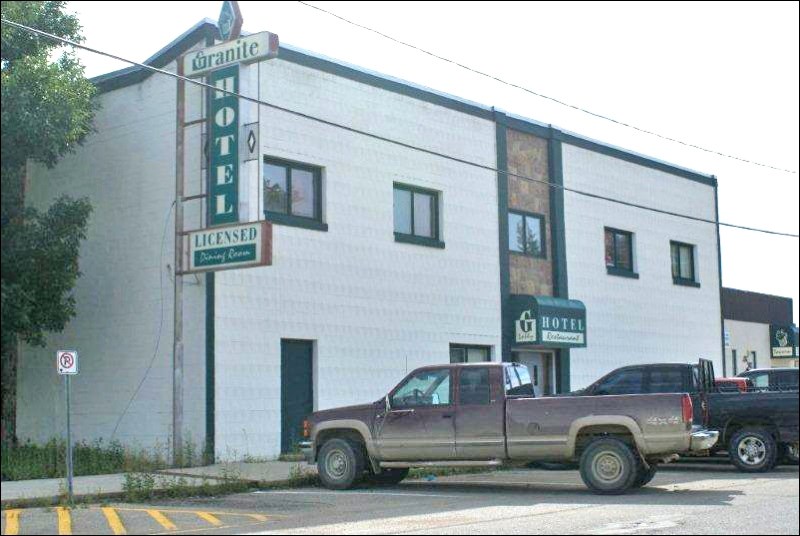

In 1887, Robert A. Copeland and W. H. Fleming bought the hotel in Grenfell with a down payment of two yoke of oxen. Eighteen years later in 1905, David Black bought the Granite Hotel from Copeland with a satchel containing $38,000 in cash.

Perhaps the value of the business had grown due to the local myth that U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt had spent the night of Dec. 14, 1901, at the Granite Hotel. A page on the hotel’s register bore the “signatures” of “Theo Roosevelt” and his travelling companions, James J. Hill, president of the Great Northern Railway; U.S. Grant Jr., son of the Civil War general Ulysses S. Grant; and J.A. Garfield Jr., son of President Garfield. Roosevelt, who had just been sworn in as president in September of that year, delivered his State of the Union address on Dec. 3, two weeks before he is alleged to have stayed at the hotel in Grenfell. On Dec. 16, he delivered a message to Congress.

For years, according to Grit and Growth, the story of Grenfell(1980), it was Grenfell’s boast that this famous name graced the register of the Granite Hotel. One man even claimed to have carried President Roosevelt’s luggage from the station to the hotel. It was a period of railway promotion, so it was thought there was an attempt to secure American capital for the building of new railway lines in Canada. Surveys were being made in the vicinity of Grenfell, located 126 km east of Regina on what is now the Trans-Canada Highway. It was suggested that perhaps Roosevelt and his friends were sufficiently interested to come and investigate the possibilities for themselves.

It’s hard to believe in today’s world of social media and “fake news,” but Grenfell’s tale of a brush with greatness was perpetuated for almost 60 years until, in 1960, a former Grenfell resident touched off a chain reaction that finally revealed the hoax. Lionel E. Curran was the “doubting Thomas.” He sent a copy of the hotel’s register to the Library of Congress in Washington DC to have the signatures of Roosevelt and his companions compared to the real ones. The library found that all but that of James J. Hill were fakes. Mr. Curran notified the Grenfell Sunof his findings, and his letter was published on the newspaper’s front page. The Regina Leader-Postpicked up the story and ran a photo of the controversial register page on the front page on Feb. 1, 1960. “The 59-year-old hoax will probably become one of Saskatchewan’s most celebrated of all time,” the Regina paper wrote.

The next morning, Saskatchewan’s Minister of Labour, Hon. C.C. Williams (CCF) contacted the Leader-Post, providing a clue to the origins of the hoax. “The signature of ‘Theo Roosevelt’ is in fact,” said Williams, “the identical handwriting of my late father who was a station agent in a small town near Grenfell at that time.” Williams said he had received a copy of the register page four years before and, not wishing to spoil the story, he said nothing. “I think the real explanation was a hockey game or curling tournament at Grenfell that Saturday night which attracted people from surrounding towns” Williams told the newspaper. “Six or seven ‘Morse boys’ [telegraph operators] got together and had some fun with the register.”

In 1980, the Grenfell local history book concluded its account of the Roosevelt myth by saying: “What better place to relax than in an up-to-date and friendly hotel in a beautiful little town like Grenfell. All we can say is that if he didn’t come it was his loss.”