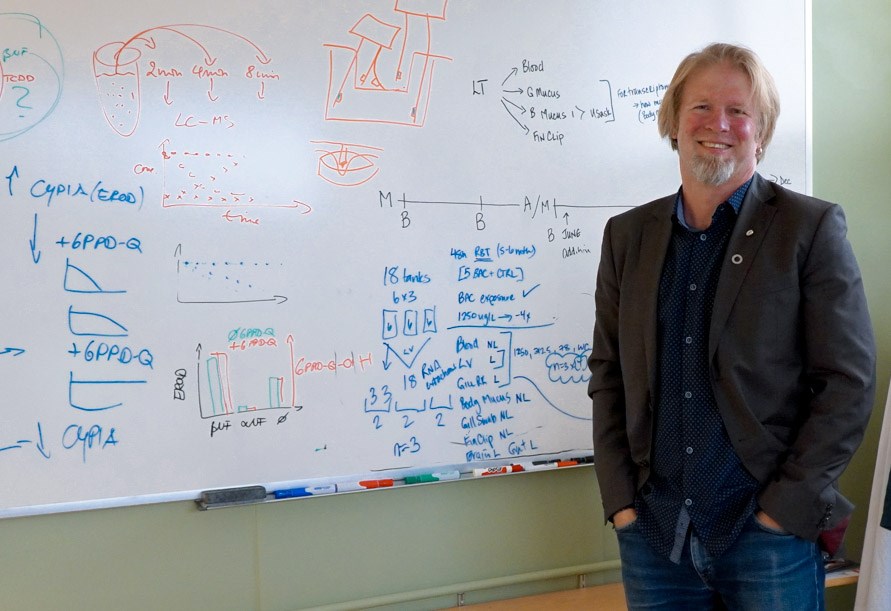

SASKATOON — Dr. Markus Hecker (PhD), professor in the School of Environment and Sustainability (SENS) and member of the Toxicology Centre at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), is no stranger to the Canadian Research Chair (CRC) program.

For a decade, he held a Tier 2 CRC in Predictive Aquatic Ecotoxicology for his research in aquatic ecosystems. Through that work, Hecker’s contributions have transformed the way toxicologists think about and conduct their research. Recognizing his status as a world leader in his field, in 2023 Hecker received a Tier 1 CRC in Predictive Toxicology and Chemical Safety.

Chemical contamination is one of the greatest threats to the planet. There are an estimated 350,000 chemicals already being used around the world today, yet over 90 per cent of them have not been tested for their toxicity. Making matters worse, each year between 500 and 1000 new compounds are registered in Canada alone, creating a backlog of chemicals that need to be tested. With so much at stake, understanding the effects of these chemicals on our daily lives is crucial, but current chemical risk assessment practices are time-consuming and expensive. They also rely on sacrificing massive numbers of live animals.

Hecker’s group is working on a plan to address these challenges.

“Traditionally in toxicology you use live animal testing in chemical safety assessments,” said Hecker. “But predictive toxicology is moving away from using living animals by exposing fish embryos, which are not considered live animals, or cell cultures to a chemical and analyzing the effects.”

Hecker is part of a larger group of researchers from North America and Europe that have been pushing a unique framework which can be used to generate toxicological results quickly, economically, and more ethically.

Get to know Hecker’s work, his state-of-the-art laboratory, and his favourite fish in these five questions with USask’s newest CRC.

“My work looks at the intersection between the environment and human health. It tries to understand the specific mechanisms by which chemicals cause alterations in biological processes, and then uses this information to predict health effects. To be toxic, any chemical or any drug you take needs to interact with a biomolecule to trigger a negative effect. That biomolecule could be anything from DNA to a hormone receptor – so we’re talking about what is happening at a cellular level.

If a large enough number of those biomolecules are affected, this will impact the cell as a whole and then — when enough cells are affected — this will result in impacts on tissues and organs, eventually becoming a system-wide issue. Similar to a domino effect.

Let’s say you are a fish, and you need to lay eggs, but some chemical affects the hormone signal that is needed to initiate the proper development of your eggs, then the eggs don’t mature, and reproduction stops.

We try to predict how much of that chemical is needed to tip the first domino, or disrupt the hormone signal, and start that chain reaction. If we can link this initial event to the final health outcome, then we can use this information to rapidly inform better chemical management practices and environmental mitigation measures to prevent these impacts.”

How has the recent Canadian Research Chair-John R. Evans Leaders Fund (CRC-JELF) investment supported your work?

“My research needs very sophisticated analytical and molecular equipment, and we have benefited greatly from the JELF partnership. I have been able to update my molecular laboratory suite and my field-based research suite to do this kind of analysis in-house. The state-of-the-art sequencing equipment allows us to better understand how whole biological systems respond to a toxic chemical and helps us do this quickly and less expensively.

The JELF partnership has given us a big upgrade. It’s like we have traded in our old minivan for a Porsche!”

What made you choose toxicology as a career?

“It’s a long story that goes back to my first class in elementary school where they ask you what you want to be when you’re an adult. At this time, I was intrigued by the ocean explorer Jack Cousteau and was fascinated with life under water. Growing up in Germany at the banks of the River Rhine, I witnessed first-hand the effects of the severe water pollution that poisoned our rivers in the 1970s.

Originally, I wanted to be a marine biologist and study fish — I have a PhD in Marine Fisheries Science. Then I stumbled into the field of aquatic toxicology while I was in graduate school. I realized that this is an area where I could make a much bigger difference.

“Sturgeon. They are such fascinating animals. As a group of species, they are around 200 million years old; they were already here when the dinosaurs roamed the earth, and they’re still around! Then, in the last 150 years humans have come along and have almost eradicated them. When I came to Canada, I worked as a consultant on a big project that studied white sturgeon, an endangered species in the Columbia River. They since have become a passion of mine. I don’t have any tattoos, but if I was to get one it would be a sturgeon.”

“We can’t stop using chemicals, we live in a chemical society. For instance, we cannot live without pharmaceuticals, but they can have significant impacts on organisms that are not the intended target, like those living in surface waters who receive these chemicals from municipal wastewater. For all the chemicals that are in use, we know the impacts or effects of only roughly 10 per cent of them, so there is still lots of work to do. For new chemicals, we can do a proactive type of assessment before they even go into development. So, we can do things differently and better.

One other important message is emphasizing the connection between human health and ecosystems. We have long looked at human health and ecological systems as separate worlds, but we cannot separate them. In fact, we are already using animals such as fish extensively in human health research, and we can see the direct connection between the effects of chemicals on fish and human health. They appear to be two worlds, but they are really one. That is the core concept of One Health but it’s something that is still often overlooked in chemical risk assessments. Our work is hoping to change that.”

— Submitted by USask Media Relations