It's an old saying, possibly dating back to Hippocrates, but it's one still commonly used in the medical profession today.

"When you hear hoofbeats, look for horses, not zebras."

Ana Felix says, "That's great, but zebras exist you know! Turn around and look at the damn thing so you know what it is. If it's striped, it's a zebra!"

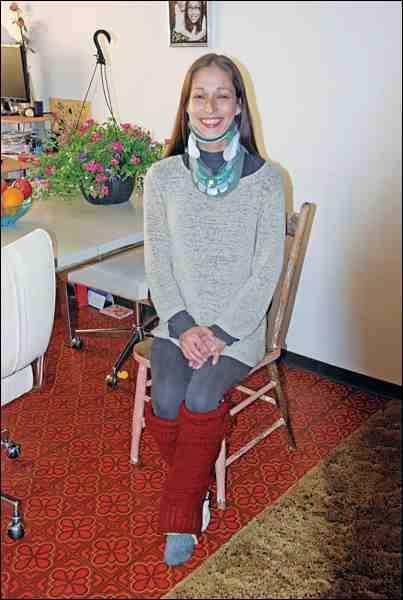

Felix has been diagnosed with a condition described as rare - Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. The Mayo Clinic describes it as a group of inherited disorders that affect the connective tissues - primarily skin, joints and blood vessel walls. In the more severe form of the disorder, vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, the walls of blood vessels, intestines or the uterus can rupture, sometimes fatally.

Thankfully, Felix does not have the vascular form. What she does have is a constant struggle to keep her joints from falling out of place.

"I can't even guess how many dislocations I have a day," she says. "Fifty? A hundred? All the time."

She's not convinced it is as rare as most people think.

"It's so silly that it gets so overlooked all the time," she says. "It's not that hard to diagnose, to be honest, once you know what you're looking for and you're familiar with it."

In Felix's case, one obvious diagnosable symptom is the fact that she can stretch the skin on her face several inches away from her cheek. She counts herself lucky compared to EDS sufferers who find themselves looking far older than their years or, much worse, have such poor wound healing any surgery can be life-threatening.

Felix, who has been experiencing symptoms of EDS since childhood, is now 34 - and has been diagnosed, officially, for only two years.

"I don't blame doctors," says Felix. She believes Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is barely touched upon during their training.

"The ones I've talked to vaguely remember someone talking about it once, but they don't ever go into it, which is how it ends up undiagnosed for so long."

Neither is there much research being done, although there are support groups online and they are working to form organizations like EDS Canada.

There are organizations for diseases such as multiple sclerosis and cancer that raise money for research, and EDS needs one, too, says Felix.

"As it stands, if I wanted to donate money to [EDS] research, I have nowhere to donate it to."

Felix says, "It's sad but true. If there's no research being done, we're all just winging it."

The "we" Felix refers to is her fellow EDS sufferers, who use the term "bendy" to describe themselves. One of the symptoms of EDS is having joints that are hypermobile. They can "bend" most of their joints to extremes because their connective tissues will stretch like rubber bands. Unfortunately they don't stretch back.

"I can't sleep on my side any more because my shoulders will pop out," says Felix.

The same goes for her ankles.

"They will be out and all over the place in the morning."

She also experiences vertebral subluxation, when one or more of the bones of the spine move out of position, creating pressure on the spinal nerves causing her to lose control over her legs.

"I've learned over time that when I wake up in the morning I clench everything and get everything back together before I move - just to be safe."

She holds herself together with a strength that is remarkable in one of her small stature.

"When stuff starts to fall apart, I tighten the muscles," she says.

Felix says her ligaments are like worn out overstretched rubber bands.

"The longer and more useless they get, the harder my muscles have to work."

She says, "I've always been very muscular. Apparently I had no choice."

Felix says Vera Bater of Battlefords Physiotherapy was the first to test her hypermobility. She was 14. In a mobility test called the Beighton score, Felix was rated at eight out of nine (her knees were minimally affected). Anything over four is "bendy," says Felix.

But being "bendy" is not the only symptom. It's just the most obvious.

Most pre-adolescent children are hypermobile. But growing up in Battleford and attending St. Vital School, Felix was more "double-jointed" than most.

"Track and field was like humiliation day for me every year," says Felix. "I would be so embarrassed."

She was sure everyone thought she was faking her frequent injuries.

"Why wouldn't they? Even I would think I was faking if I was them. I just got hurt so often, and my ankles were always turning on me."

By the time she was in Grade 2, she was twisting them regularly.

"I was spraining them nearly every day," she says. "Of course that gets ridiculous and you look like the kid who's just trying to get attention so I would straight out hide it because I was embarrassed I'd hurt myself again."

What did she do?

"You just suck it up and keep going."

It's not that she didn't have any fun being "bendy." She remembers trying to stuff a friend into a box. He saw her do it and saw no reason why he shouldn't be able to do the same. Nor did she.

"Thank goodness we didn't hurt him."

People with undiagnosed EDS sometimes find themselves doing these kinds of "party tricks," not knowing they are setting themselves up for future pain and injury.

"Every time you extend [a joint] and make it worse, it just stretches it more and more the joints aren't going to recover, they don't know how, they aren't capable of it."

EDS can take other kinds of toll as well. Felix says most people with EDS get diagnosed with depression or anxiety problems early on in life, even in childhood. But what seems like anxiety isn't, she says.

"It turns out you don't have anxiety issues. It's your brain that's actually having difficulty regulating your entire autonomic nervous system."

For example, she says, as a kid she was told 'you have a nervous stomach,' because she had a lot of nausea.

Now she realizes it was part of the autonomic dysfunction that goes along with EDS.

Another symptom is orthostatic intolerance. You don't have to have EDS to experience orthostatic intolerance, but Felix explains "bendy" people often have it because blood vessels, being made up of connective tissue, will balloon under pressure, causing fainting, near fainting and blood pooling.

"A lot tends to be written off as anxiety or just moving too fast," says Felix. "What I thought for years is 'isn't everybody like that?'"

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, or gerd, is another symptom commonly experienced by people with EDS, and another one that is common outside the EDS population as well.

Mitral valve prolapse is another. Often called a heart murmur, the valve between the heart's left upper chamber and left lower chamber doesn't close properly. Felix does not have MVP, but even those who don't are recommended to watch carefully, just to be safe. Recently a member of Felix's online support forum, a woman in the United Kingdom, died of a random aortic dissection. Not until her death did it become clear she had the vascular form of EDS.

Perhaps the most pervasive of EDS symptoms is pain.

Felix says she is at the point now where her exceptionally high pain threshold has become harmful, because it's much easier to injure herself, or push herself too far.

"We tend to have such high pain tolerances because most of us spent our whole lives with various doctors telling us 'it's in your head,' 'it doesn't hurt that bad,' or 'take a Tylenol,' so we build up these ridiculous pain levels," says Felix. "I don't mean to complain, that's just how it is."

By the time she was 14, she started showing signs of fibromyalgia. The physician she approached about the pain she was experiencing was less than helpful.

"You start to feel like maybe you are crazy, maybe you are making it up," she says.

"As a kid, I totally thought 'I guess I'm just kind of wimpy.'"

About 10 years ago, a specialist looking into her hypermobility told her to take it easy and to not over-extend her joints, but there was no mention that with joint hypermobility other tissues are affected too.

She continued to research her other issues, and eventually made a suggestion to a new physician.

She told him, "I don't mean to sound like one of those people who say I think I have this thing I saw on the Internet, but"

Her doctor did some tests and sent her to a geneticist for confirmation of the diagnosis. Her father, Rick, went along. Since then her son Keenan has also been diagnosed with EDS and her daughter Aiden, her children with Jeremy Bellows, is being monitored for scoliosis.

EDS is hereditary, and both her parents have joint hypermobility.

"It comes down on both sides, that's how I ended up so steeped in it," says Felix. "I won the genetic lottery."

Her two brothers are also affected with joint hypermobility and her sister has Chrohn's disease.

"IBS [irritable bowel syndrome] is another thing that goes along with EDS," says Felix, as are fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Weight management is an additional issue.

"Those of us who are smaller or bigger have slightly different struggles. With my set of genes it's always been a struggle my entire life to gain weight if I get sick it's a real worry because I don't have any weight to lose."

At 5'2'', Felix weighs about 90 pounds.

"I was always tiny, but I'm smaller now than when I graduated high school," she says.

It's harder to keep the weight on with the household to take care of, work to do and children to care for.,

Felix's muscles don't get a chance to relax. They are constantly burning calories, even in sleep.

"I purposefully clench up while I am sleeping, or before I shift."

Each time, as she says, "There's another handful of calories. I can't even eat enough."

Neither can her son, she says. Ironically, at a time when he's writing school reports on healthy eating, he and his mom have orders to eat as much as possible, including foods high in sugar and fat.

Felix says her doctor reminds her it's the process of breaking down sugar that is unhealthy, but they use it up so fast it never makes it through that process.

While a balanced diet is just a dream, balance in the rest of Felix's life is an urgent reality.

People with chronic conditions often learn to use a spoon theory for energy levels. They start the day with so many spoons, and they budget their energy in such a way as to not run out of spoons.

"When I was a kid I had already figured this out, and as a child I used to use money. It was a finite amount I was comfortable with," says Felix. "I'd act like this is the money I have for today to work with, what do I need to buy? I need to buy supper, I need to buy a shower you have to prioritize."

One of the most important things Felix has learned is, just because you want something done, that doesn't mean it's going to happen.

"It gets to be a juggling act," she says. For example, if she is going to travel, she'll start planning two weeks ahead, because it means making sure she has the medications she needs, and the braces she needs.

"I have two bags of braces." She has ankle braces, knee braces and two kinds of neck braces.

How much to wear the braces is also a balancing act. Too often, and the muscles start to weaken.

"Every little thing is a balancing act - 'Am I too tired to do this or do I need the exercise?'"

Felix, despite having a lively sense of humour about her circumstances, says, "It's very frustrating to be honest. I'm very lucky I don't have any dangerous life threatening types of things, and I so appreciate that, however it is just solid obnoxious. All the time. Twenty-four hours a day."

Many EDS sufferers do develop depression and anxiety, apart from the autonomic variety, as people might with any kind of chronic illness.

"As a teenager I struggled with depression," says Felix. In fact, she graduated high school two years late because of what was assumed at the time to be a nervous breakdown.

"I sought treatment, but it never occurred to me for a second to wonder why I was depressed, that there was an actual cause."

It taught her important skills.

"You learn breath control and you learn to prioritize and you learn not to think about things past eight o'clock if you want to be able to sleep at night."

You have to take care of yourself, says Felix.

"That's one of the biggest positives I've got out of this, is that it's really forced me to figure things out that maybe other people never figure out, sadly, or it takes them their whole lifetime, or they have to go through years of therapy."

Currently, Felix works at minding children in her home, bearing in mind they have to be old enough and independent enough to match up with her physical limitations. She knows that could change in the future.

She's had other jobs outside the home, even taking a dental hygienist distance program, getting top marks. But her body couldn't physically handle the work.

"Even holding the suction, the easiest thing you can do in that position, started to give my shoulders problems, then wrist pain, and again with the stupid RSIs [repetitive strain injuries]."

Felix's home life includes therapy for those "stupid RSIs" and other issues.

"I've gone through physio for nearly every part of my body and at any point during the day I'll be doing something for physio," she says. "While I'm doing dishes I can do neck exercises, or crunch my shoulders, or stand like a flamingo."

It seems she's always been her own therapist and personal trainer out of self-preservation.

"I just learned over time I have to do it. The funny thing is, as I started going to these professionals, all these things were things I had been doing automatically since I was a kid."

She is relieved to have a confirmed diagnosis when it comes to seeing to her children's future and their own health.

"Nobody will be telling them to just walk it off, or whatever kind of ridiculousness," says Felix. "We know better now."

In telling her story, Felix hopes to make people more aware of EDS.

"When I talk about it, people say 'I know someone like that.'"

She believes there are many more EDS sufferers than are ever diagnosed. But she hopes that's changing as awareness increases. Her own children's issues have, through going to school, made more people aware. One health worker has asked Felix what kinds of things to look out for in children, to which she says to watch for kids who are "super bendy past 12."

If, past that age, they can still bend over and put their hands flat on the floor with their knees straight, they should be assessed, says Felix.

She's also encouraged by the interest being shown EDS groups such as the online EDNF.org and EDS Canada. She believes, also, there is interest being shown in including more information about EDS in medical schools.

Felix has made contact with other "bendy" people through these groups and through Facebook.

"Facebook has been a giant support group because at one point I thought I must be totally crazy."

Although there are studies that say Internet use can make people sad, there are EDS sufferers who were contemplating suicide before they found online support, Felix says. It's important to know "people understand you and believe you."

At this point, Felix doesn't know of any other EDS sufferers in this community, but if the incidence is one in 2,500, she's sure they are out there and she would like to start a local support and awareness group.

There may be people with EDS who, like her, think their symptoms are in her head, or who don't know everyone isn't experiencing the same things.

"In my case, normal turned out to be completely abnormal," she says.

Felix also believes furthering awareness may also bring the connectivity of EDS to other disorders under more scrutiny. Could it be the unknown root behind other disorders that may be getting treatment but that no one is asking questions about, she wonders.

"You have to be willing to move past that, otherwise we are not ever going to truly make any progress, are we?"

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)