MOOSEJAWTODAY.COM — Saskatchewan’s privacy commissioner has ruled that the provincial coroner’s office does not need to provide media with comprehensive reports about two Moose Jaw deaths because the documents contain personal information.

The Moose Jaw Express submitted two freedom of information requests in early January to the Saskatchewan Coroner’s Service (SCS) asking for all investigative documents and autopsy reports about the deaths of a and

On Jan. 11, the SCS denied the request for all records about the 40-year-old’s death, saying provisions in The Coroner’s Act, 1999, and The Coroner’s Regulations, 2000, prevail over The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FOIPPA).

“As chief coroner, I (Clive Weighill) do not consider it either appropriate or in the public’s interest to release the requested reports in advance of the public inquest; therefore, your request for these records is denied,” the SCS’s letter said.

.

Meanwhile, on Jan. 13, the SCS provided the Express with a report about LeMay’s death, but the document was so heavily redacted — all personal information was removed — that it revealed nothing about the man’s death or how he died.

The office indicated that provisions in The Coroner’s Act, 1999, The Coroner’s Regulations, 2000, and The Health Information Protection Act (HIPA) prevented it from releasing a complete — and unredacted — document.

“As chief coroner … subsection 27(4)(e) of HIPA prevents me from sharing any personal health information with you as you are neither the decedent’s immediate family, close personal friend or health professional,” the letter said.

Furthermore, the SCS said, based on sections in the Act and HIPA, “it was neither appropriate nor in the public interest to release the contents of the autopsy report given the sensitive and private nature of this medical test,” nor was it appropriate to release contents of the third-party investigation since that could negatively affect an ongoing investigation.

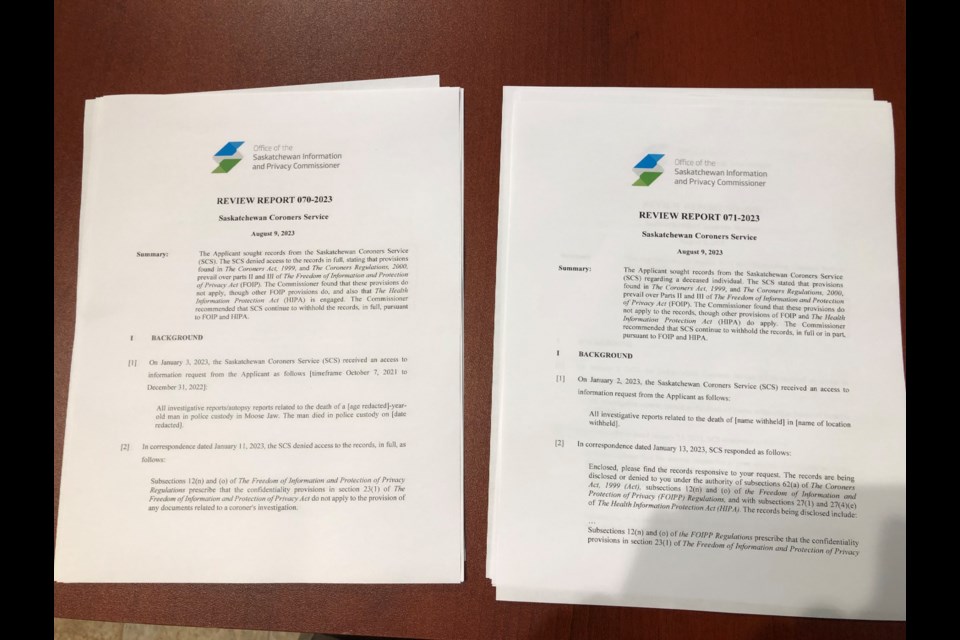

The Express asked the Office of the Saskatchewan Information and Privacy Commissioner to review the SCS’s decisions, and after several months, it provided two written responses in mid-August.

Commissioner Ronald Kruzeniski identified 164 pages of reports about the 40-year-old’s death, including a final autopsy report, an independent observer report, four police service reports and an EMS report. Meanwhile, he identified 148 pages of reports for LeMay’s death, including an independent observer report, a police agency report, the autopsy report and the coroner’s report.

Kruzeniski determined that he had jurisdiction to review both cases because subsections of FOIPPA and HIPA were “engaged” in the matters, including the fact the SCS is a government institution under FOIP regulations and is a “trustee” under HIPA, while both reports contain personal information including how the men died.

Furthermore, the privacy commissioner determined subsections 23(3)(m)(n) of FOIP and subsections 12(n)(o) of the FOIP regulations applied in these matters.

He noted that section 23 of FOIPPA “ensures that the fundamental rights enshrined in FOIP are given proper deference when interpreting legislative intent as to its application in conjunction with other statutes. This primacy clause is a strong expression of legislative intent and a tool for ensuring public policy objectives are met.”

Kruzeniski pointed out that “it is reasonable” for SCS not to release any information about the 40-year-old’s death under section 62 of The Coroner’s Act, 1999, because of the upcoming inquest.

The privacy commissioner also reviewed whether the SCS should continue withholding certain records of both cases under FOIP regulations. He ruled that it could since the regulations state an individual’s personal information can only be released 25 years after that person is dead.