Ben Davis, who began teaching as a sessional instructor for the IshKaabatens Waasa Gaa Inaabateg Department of Visual Art at Brandon University in 2008, has created a multi-model project unpacking, exploring and encouraging discussion about the devastating impacts of resource extraction in natural spaces. He recently received a $21,800 Research and Creation grant from the Canada Council of the Arts to support his ongoing project “extracted,” which focuses on the consequences of resource removal in Uranium City, a town in northern Saskatchewan.

“It’s important to try and find avenues which might interest many different people. You can’t just hit them with one style of painting or one sculpture. I think you have to create footholds or doorways which they can sort of gradually move into and feel some inclusion,” said Davis, who currently teaches in BU’s English for Academic Purposes program and supervises education practicums.

“It has a common critical framework and the idea is that Uranium City is just one instance of something that is taking place everywhere.”

While he cannot speak directly for the people affected by the activity, he can speak more generally about the consequences of climate change for people in many different communities around the world.

Action is needed to mitigate the damaging effects of the climate change crisis — including the gradual phasing out of fossil fuels. He added it is an important moment for Canada as there is a convergence between truth and reconciliation, and the climate.

There is a responsibility to address climate change, especially because Indigenous communities will be the first affected by the crisis and communities can offer insights on how to live in harmony with the land.

“The rest of us have a massive duty to learn and catch up.”

Davis’ art project, “extracted,” began out of a conversation with criminal justice scholar Kevin Walby.

“We realized that the way we were speaking about land intersected. We talked about layers and history and the stuff that you can’t see — the social terrain of land which often is missed in the photographs that people take,” Davis said.

“Dr. Walby looked at the site through lenses of social and environmental justice. Land has long been a central focus of my practice, as I purposefully unsettle the physical and socially constructed terrain of a location, also through lenses of social justice, eco-aesthetics, and postcolonial theory. It intersected well with Dr. Walby’s research.”

He was inspired to capture these experiences in a multimedia format based on his interest in counter-visual methodology, a practice of upending the reliance of photographs alone to explore a theme, story or topic.

“You begin to think about ways to aggregate visual images. You begin to think about how you can make people question what they’re looking at and what they assume.”

Walby shared some of his photographs of mining sites and the land surrounding Uranium City. The images presented beautiful and “pristine” land that appeared untouched, Davis said, but data showed the land and water in the area were toxic.

The destruction of the environment was the consequence of large-scale resource extraction, including uranium and gold, and in turn, came to affect the people living in the area.

“I was interested in not only this idea of these photographs [that] really don’t show the reality of what has taken place, but also the impact on this place for people as well,” he said.

His goal was to create art that inspired people to dig into what they are seeing. This involved using less obvious and untraditional materials.

Davis said this way of thinking inspired him to use bitumen, an extracted resource, in his art.

He has put the funds from the grant toward his studio and is using the space to experiment with the product, but it is challenging because bitumen never dries and can create cracks and fissures in a painting, slowly destroying the creation.

“I thought what ... if we use bitumen so it slowly destroys the paper, and people can question why the painting is being destroyed, and they relate that to bitumen,” Davis said.

An added layer to encourage people to unpack the images presented has been engaging in the history of arsenic — an element used in Victorian times and beyond, even though it was known to be poisonous, Davis said, in a situation very similar to what resource extraction does to the earth.

“That’s a very colonial way of seeing the world. We know it’s wrong to oppress people. We know it’s wrong to take their land. But you know what? It benefits us financially and it helps us.”

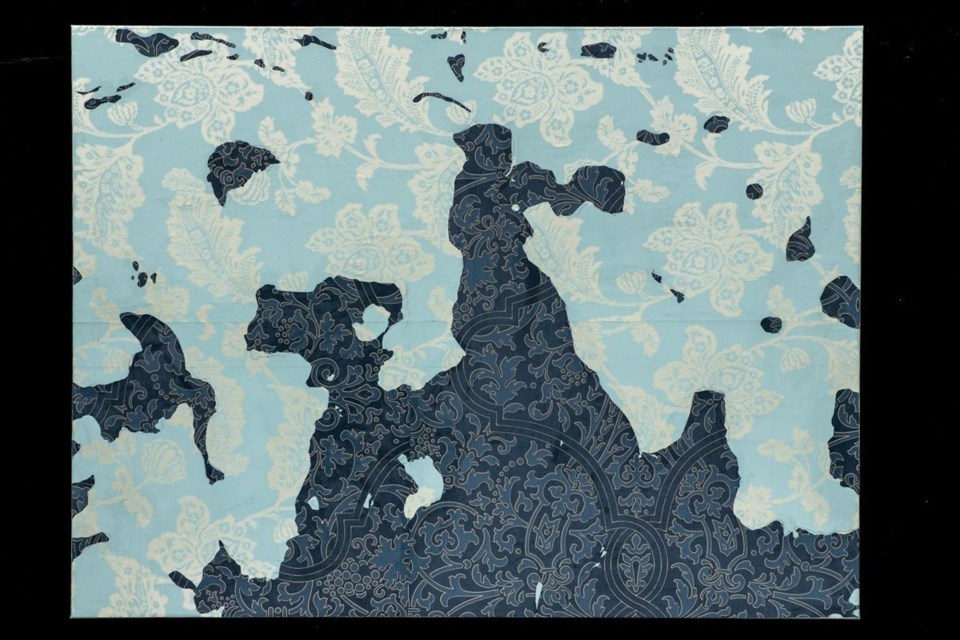

He references this through collages made of Victorian wallpaper designs. The Victorian designs also subtly encourage people to think about colonial history in Canada and the efforts to cover up the impacts of resources extraction by the provincial and federal governments.

“Essentially, they were trying to wallpaper over the damage they had caused,” Davis said.

“It also had me thinking about the whole dirty history of colonialism where they force their own particular understandings and their ways of being onto Indigenous people. They reimagined land as they understand it and don’t honour and respect the understandings, the rituals and the beliefs of the Indigenous people.”

One of the featured images of “extracted” was created using satellite images of an area near Uranium City and Victorian wallpaper.

The final strand of “extracted” was incorporating recordings provided by Walby documenting the experience of those affected by Uranium City, including a contemporary Indigenous community member and a settler.

The resident spoke to the impact of the mine, the loss of community and the ongoing effects on the environment caused by resource extraction. It was critical to include these voices because they are living through the events and he wanted to ensure their stories are heard by others.

These recordings are included in the project for guests to listen to when visiting “extracted.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report noted there is much to be gained by listening to those most affected by environmental damages such as those caused by human decisions. The project served as a way to bring voices, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, together to showcase the slow death of Uranium City to a wider audience.

“Rather than just admiring the finesse of a painting or sculpture, it’s actually questioning the materiality of it,” Davis said.

To draw visitors into the project when exhibitions of “extracted” open, participants actively engage in the artistic process by tracing images of Uranium City.

While some parts of the project have been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the tracing has begun as collaborative projects during Davis’ residencies in Hospitalfield House in Scotland and at Banff, Alta.

The planet’s unfolding environmental crisis is an emergency, he said, and he wanted to create artwork that would slowly vanish like the land disappearing because of resource extraction.

“I saw some photographs of the peeling wallpaper in Uranium City, in the school and in homes, and I thought about tracing paper.

“I devised this way of using tracing paper where people come together and collaboratively trace from images, which look like beautiful untouched land but actually are toxic.”

As participants trace, they listen to the lived experiences of Uranium City residents through recordings.

Davis said the exhibition prompted a deep discussion between tracing participants. With their permission, Davis recorded those discussions for others to hear as they themselves interact with the project.

“I’m making some pieces that I have authorship to, but at the same time, one of the big goals is actually to create opportunities for participation in discussion. It can happen many times with different people and gradually these pieces grow and these rolls of tracing accumulate.”

Davis hopes the engagement will inspire small steps in acknowledging, engaging and tackling climate change.

“They participated in this really important conversation about the environment and climate crisis.

“It’s meditative, but it’s also a very positive thing because you feel like you’re quietly accomplishing something.”