WESTERN PRODUCER — Spring is one of my least favourite times of the year when it comes to trying to forecast weather, while also being one of my favourite times of year.

I love the fact that it is warming up — the older I get the more I find myself thinking about how I can end up spending most of my winters in the tropics. I love the melt season (usually) as the little kid in me is allowed to come out when I get to play in the water, making sure things are draining properly. The only difference is I get to use bigger tools than when I was a kid, and I actually have a “reason” for playing in the water. I don’t like it when there is so much melt water that I have serious issue to try and deal with. Finally, there is something special about starting plants and getting the greenhouse going at this time of year.

On the downside, as I pointed out, trying to figure out the weather in the spring can be a real pain in the … you-know-what! From the big picture point of view, the atmosphere is heating up towards summer-like temperatures in the south while in the north, winter’s cold temperatures are still in place.

The weather across our region is mostly caused by these two air masses battling it out for dominance and it is at this time of the year that they are most evenly matched. This is why we can see some of our biggest storm systems at this time of the year, and it is also why forecasting can be so difficult — often the atmosphere just can’t make up its mind on whether it should be summer or winter.

There is more. On top of the large-scale battle between warm and cold air we have a couple of smaller scale phenomena that can play havoc with spring weather and weather forecasting.

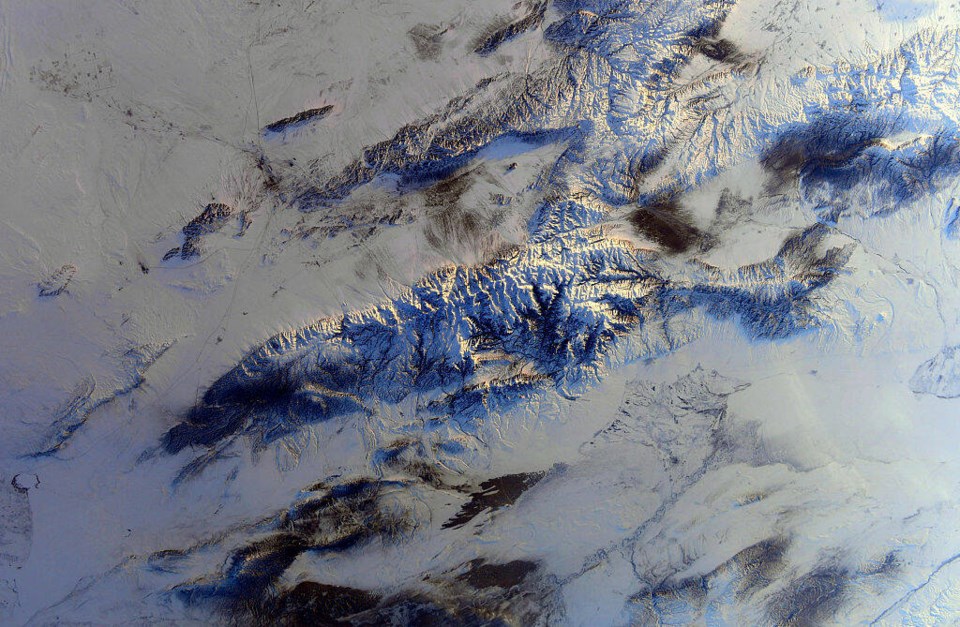

The biggest player in this smaller battle is the cold ground, or rather the cold snow sitting on the ground. Snow reflects sunlight which would, without snow cover, be absorbed by the ground and turned into heat. So, the reflectivity ( ) of snow helps to keep us cooler. Snow is also nature’s air conditioner. It’s frozen water, and the effect of that is obvious.

To melt snow it takes energy, lots of energy, and that energy comes in the form of heat.

Just how much energy does it take? Well, to melt snow you first need to warm the snow to just below the freezing mark. It takes about 2000 joules per kilogram of snow to warm it one degree Celsius. So, if we take an example of one kilogram of snow at -10 C it would take 20,000 joules of energy to warm it up to the freezing or melting point. Now, to get the snow or ice to change phase into water takes a lot more energy. This seeming little push of temperature from just below freezing to just above freezing takes about 33,500 joules per kilogram — more energy than it took to warm the snow up by 10 C.

Now you can see why areas with no snow cover can be significantly warmer than areas with snow cover

This isn’t the only thing that plays havoc with spring weather. The second influence is something known as a temperature inversion. This occurs when warm air moves into a region, but it rides up and over a very thin layer of cold air that in essence gets stuck at the surface.

Inversions, with warm air over cold air creates a very stable environment and can last for long periods of time. We often see this happen in the spring thanks largely to the cooling effect of all the snow on the ground.

Sometimes it is a very large scale event where ground temperatures are cool or cold, say in the -10 C range, while only a couple hundred feet up temperatures can be as warm as +10 or +15 C. This is why regions that are higher in elevation can , while the rest of the region is stuck in the cold.

Along with being a large scale event, this pattern often develops due to local topography. The most commonly affected regions are valleys or depressions. Whether the valley is narrow and deep or wide and shallow, cold air can settle into these low points and with the tendency for warm air to rise, it can sometimes be difficult for the warm air to push the cold air out. While this setup creates colder than expected temperatures across the affected region, it also can have an impact on cloud cover.

This warm air over a shallow layer of cold air will often result in overnight fog which then transitions into low clouds that can sometimes stick around for days. This mostly happens in areas that have shallow wide valleys or depressions such as the Red River Valley in Manitoba.

Fortunately for those of you who live in these types of regions, winds are often strong enough to eventually scrub out the cold air allowing the mild air to finally flood in. When this does happen, it can often occur very quickly.

Try to remember these different weather havoc sources when the forecast is calling for a 10 C high three days from now and then switches it to a 2 C forecast 12 hours later. That’s just the weather models trying to figure things out.

About the author

Daniel Bezte is a teacher by profession with a BA (Hon.) in geography, specializing in climatology, from the U of W. He operates a computerized weather station near Birds Hill Park.

Related Coverage